Ang Lee's greatest strength as a filmmaker is his affinity for minutiae. As his repressed, internal characters rarely lend themselves to dramatic broad strokes, the filmmaker instead allows the narrative weight of his films to reside in a painstakingly precise accumulation of details, his best films arriving at simple images - a family waiting on a train station platform, a jacket carefully hung on a closet door - that have a devastating emotional impact. On the surface, Lust, Caution is a showcase for the director; it's a film where lipstick traces on a teacup weave their own sensual spell. Lust, Caution is Ang Lee's most visually handsome film, but it's also oddly cold and unengaging - too remote to generate much real suspense or eroticism, it ultimately fails to deliver on the promise of its seductive surfaces.

Ang Lee's greatest strength as a filmmaker is his affinity for minutiae. As his repressed, internal characters rarely lend themselves to dramatic broad strokes, the filmmaker instead allows the narrative weight of his films to reside in a painstakingly precise accumulation of details, his best films arriving at simple images - a family waiting on a train station platform, a jacket carefully hung on a closet door - that have a devastating emotional impact. On the surface, Lust, Caution is a showcase for the director; it's a film where lipstick traces on a teacup weave their own sensual spell. Lust, Caution is Ang Lee's most visually handsome film, but it's also oddly cold and unengaging - too remote to generate much real suspense or eroticism, it ultimately fails to deliver on the promise of its seductive surfaces.Wednesday, April 30, 2008

You and your appointment.

Ang Lee's greatest strength as a filmmaker is his affinity for minutiae. As his repressed, internal characters rarely lend themselves to dramatic broad strokes, the filmmaker instead allows the narrative weight of his films to reside in a painstakingly precise accumulation of details, his best films arriving at simple images - a family waiting on a train station platform, a jacket carefully hung on a closet door - that have a devastating emotional impact. On the surface, Lust, Caution is a showcase for the director; it's a film where lipstick traces on a teacup weave their own sensual spell. Lust, Caution is Ang Lee's most visually handsome film, but it's also oddly cold and unengaging - too remote to generate much real suspense or eroticism, it ultimately fails to deliver on the promise of its seductive surfaces.

Ang Lee's greatest strength as a filmmaker is his affinity for minutiae. As his repressed, internal characters rarely lend themselves to dramatic broad strokes, the filmmaker instead allows the narrative weight of his films to reside in a painstakingly precise accumulation of details, his best films arriving at simple images - a family waiting on a train station platform, a jacket carefully hung on a closet door - that have a devastating emotional impact. On the surface, Lust, Caution is a showcase for the director; it's a film where lipstick traces on a teacup weave their own sensual spell. Lust, Caution is Ang Lee's most visually handsome film, but it's also oddly cold and unengaging - too remote to generate much real suspense or eroticism, it ultimately fails to deliver on the promise of its seductive surfaces.Sunday, April 27, 2008

Thursday, April 24, 2008

We are running out of time.

Opening in 1938, Coppola's film finds as his surrogate a 70-year-old linguistics professor, Dominic Matei (Tim Roth), whose plans to end his own life are interrupted by a bolt of lightning (an unintentionally hilarious moment). As he recovers in a local hospital, Dominic is informed by his doctor (Bruno Ganz) that he is undergoing a remarkable physical transformation - while his mind still contains the memories and knowledge of an elderly man, his body has rejuvinated itself, transporting him to the physical state of his youth. It's a concept that Coppola has a good deal of fun with in its early stages, turning Dominic into a kind of egghead superhero who uses his supernatural cognitive powers to evade Third Reich scientists eager to exploit his mysterious abilities while also using his rediscovered libido to bed a Nazi spy (Alexandra Pirici) - it's fantastically pulpy stuff, and Coppola's fearless enthusiasm is infectious.

The narrative grows more complicated as time progresses and Dominic encounters Veronica, a similarly gifted young woman (Alexandra Maria Lara) who reminds of his long-lost love and is given the opportunity to finish his life's work, the discovery of a "proto-language" Dominic believes will return humanity to some essential form. Adapted from a novella by religious historian Mircea Eliade, this is heady literary material for a film, and it's a pleasure to watch the director mirror his protagonist in a story that weaves between genres and forms and touches upon philosophy, theology and mythmaking with the wide-eyed enthusiam of a 20-year-old liberal arts student. The filmmaker's uncanny sense of rhythm and the employment of recurring symbols (roses, in this case) remind of his once-unparalleled grasp of such filmic flourishes. If Coppola's goal was to start over than he's succeeded - the film has the stylistic abandom of a first-time director - and yet it's his maturity, his willingness to embrace his film's hermetic interior world, that leaves a lasting impression.

While the ideas on display here are worthy of discussion, they don't always translate effectively to cinema. The ongoing dialogue between Dominic and his double (also Roth), composed of matching shots of the actor and canted angles, reminds too strongly of Gollum to work and quickly grows irritating. And while Coppola's earnestness is admirable, it sometimes leads to unfortunate guffaws, as when Dominic matter-of-factly informs Veronica "that stranger in your dream was probably Shiva." The conflict that drives the final part of the film - whether Dominic should complete his work at the expense of Veronica's life or choose love - is interesting conceptually but lacks dramatic impact. Most of this is probably attributable to Coppola's long absence from filmmaking; I can't wait to see his next film to find out if he's gotten the lead out.

The sweetest and most enduring thing about Youth Without Youth is how it works as a return to forgotten cinematic languages. Shot in hi-def, the film nevertheless begins with old-fashioned title cards and journeys through noir, sci-fi and romantic scenes all filtered through a nostalgic haze. In paying homage to the movies of his youth, Coppola succeeds in making his film a tribute to the childlike wonder of cinemagoing - the idea of film-as-magic-show he's returned to over the years - that reminds that Coppola is perhaps cinema's greatest living romanticist. The clunkier aspects of Youth Without Youth are made forgivable by its willingness to fail in search of a cinematic proto-language, an aim at once grandiose and humble. More than anything, Youth Without Youth lingers in the mind as the work of a once-lost cinematic master who has found his voice again, and (hopefully) the promise of more masterpieces to come.

Tuesday, April 22, 2008

The Trim Bin #68

- Walter Chaw's latest post from The Trench: cranky, arrogant and genuinely provocative.

- CHUD's You Got It All Wrong series: cranky, arrogant and completely pointless.

- Culture Snob has a fascinating take on the elusive appeal of The Shining (thanks to Film Experience for the link). This is why The Shining is one of my very favorite movies - like most of my favorites, it continue to reveal itself to new interpretations and approaches many years after its release.

- Tried to write a top 10 of the best transformation scenes per the request of my friend Michael, but I could only come up with 9 (and I only had much to say about 3 or 4). The list was exclusively made up of '80s movies, the golden age of latex, prosthetics and K-Y slime following the apex of the subgenre - when it comes to transformations, there's An American Werewolf in London and there's everything else. Any other favorites worth mentioning?

- Finally, with There Will Be Blood hitting DVD last week and a wider audience discovering its insane brilliance, the glut of Plainview parodies and milkshake jokes is only going to keep growing (see Patton Oswalt's prediction that Plainview will be the go-to impersonation for hack comics). This one is my favorite: it's simple, I couldn't tell you why it's funny, and I can't stop watching it:

Friday, April 18, 2008

Wednesday, April 16, 2008

Such was McTeague.

Saturday, April 12, 2008

Thursday, April 10, 2008

Pimps don't commit suicide.

Donnie Darko is arguably the best first feature this decade, a fusion of teen angst, metaphysics and late-80s junk culture. Thrillingly trippy and oddly moving even as it uncannily anticipates our post-9/11 paradigm shift, Donnie Darko deserves its cult status and signaled great things to come from writer/director Richard Kelly. My lingering affection for Kelly's debut was enough to shrug off Cannes audiences, critics and an indifferent audience in the hope that his second film would prove to be a misunderstood gem. And perhaps the failure of Southland Tales - and fail it does, miserably and interminably - is evidence that Kelly shares his audience's faith in himself. Southland Tales is the grating, self-satisfied byproduct of a second-time director attempting to live up to his premature "visionary" status and failing completely. I'm tempted to compare Kelly to Michael Cimino, except Heaven's Gate is at least a visually beautiful film, whereas Southland Tales is an ugly, obnoxious mess.

Meant as a Breakfast of Champions for the 21st century, Southland Tales has more in common with Alan Rudolph's disastrous adaptation than the book or any of Vonnegut's work (or the work of Andy Warhol or Thomas Pynchon, to name a few of the artists that Kelly has cited as influences). Kelly apes Vonnegut's self-reflexive narrative structure but cannot match the author's wit or humanity. The unwieldly story of Southland Tales, set in an alternate 2008 where WWIII is in full swing, is a portrait of the apocalypse as seen through the eyes of amnesiac action star Boxer Santoros (Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson), his porn star girlfriend Krista Now (Sarah Michele Gellar) and cop Roland Taverner and his neo-Marxist brother Ronald (both Sean William Scott). Their intertwining fates are set against a backdrop of an alternate LA populated by a cast of revolutionaries, celebrities, and partygoers tangled up in a plot that encompasses homeland security, the energy crisis, race relations and teen horniness in an epic venting of one budding auteur's spleen. It's possible that the collision of social commentary and disposable culture could make for a fascinating portrait of the zeitgeist (it already has - it's called Until the End of the World and it's great), but Kelly restlessly moves from one knowingly crappy setpice to the next before his ideas are able to take any discernible shape. Just as each location is defined by its sense of clutter, the scenes pile on top of each other in an increasingly abrasive manner; it's clear the approach is intentional, and this hyperbolic approach may be a smart choice for contemporary satire. The problem is Kelly's failure to connect his clutter in a cinematically meaningful way - lacking a coherent aesthetic sensibility, lumbering from one pointless scene to the next, stopping for the occasional inexplicable musical number Southland Tales is supposedly about chaos and meaninglessness but only succeeds in contributing to the endless stream of noise it supposedly skewers.

The biggest disappointment of Southland Tales resides in its most promising conceit, a cast populated by B-to-D-list celebrities ranging from Wallace Shawn to Zelda Rubenstein to Christopher Lambert. There's a wealth of satirical material to be found in my generation's curious veneration of kitsch, and I'd hoped Kelly's cast list indicated a deeper explanation of the connection between pop culture and regression touched upon in Donnie Darko's Smurfs debate. But the presence of sitcom and B-movie actors playing their roles straight not only condescends to the cast (Jon Lovitz, playing a racist cop here, was previously used in a serious role in Todd Solondz's Happiness to greater and more subversive effect) but only succeeds in reaffirming the hipster detachment Kelly is supposedly criticizing. He might as well have taken the joke further, into the realm of pure trash absurdism - picture a Mexican standoff between Jaleel White, Dom DeLuise and Elvira - but since there is no joke beyond the fact of the B-list ensemble, Southland Tales deteriorates into a series of derisive snickers of recognition while leaving open the question of what exactly Bai Ling is doing in the film besides smoking and posing (I guess the answer's in the question). Kelly reduces his entire film to the same "everything is crap" mentality, which begs the question of why we need this demonstrated for two-and-a-half mind-numbing hours; he's not the first artist to demonstrate contempt for his audience and medium, but he is the first to give the world Justin Timberlake quoting (and misquoting) T.S. Eliot and Revelations with a straight face.

Southland Tales does contain a few strong ideas - the home-movie depiction of a nuclear attack that opens the movie, Santoros' description of his self-penned screenplay The Power, Krista's hit single "Teen Horniness is Not a Crime" - that had me holding out hope until the very end that Kelly was going somewhere with all of this. Then the movie made a blatant attempt to tie itself to Mulholland Drive, reverted back to some leftover ideas from Donnie Darko, resolved its central conflict with a frigging rocket launcher and cut to black after the most laughably pretentious final line I can remember. If Kelly rebounds with his next film, an adaptation of Richard Matheson's The Box, than Southland Tales may be remembered as a blip in an otherwise interesting filmography. But the geniunely disconcerting comments by Kelly fans on his MySpace page ("Southland Tales is so amazing in every single way") concern me - is it possible that Southland Tales will ride the coattails of Donnie Darko to default cult status? Or, much more disturbingly, is there actually something in this mess that is speaking to the kids (further evidence that we increasingly need to be bludgeoned into submission in order to feel anything)? Whatever the case may be, when the emotional apex of a film consists of Mr. Dick-in-a-Box pouring beer on his head, something has gone horribly wrong.

Wednesday, April 09, 2008

Paging Mr. Herman

It's a weird thing to look at yourself on the big screen. Yes, it turned out my mug was impossible to cut from 21 - I'm all over the place, specifically in the two classroom scenes that bookend the movie. And despite my fear of following in the footsteps of Pee-Wee, my friends and family assured me I did an excellent job of sitting, staring, taking notes and laughing at Kevin Spacey's terrible jokes. It's been a year since I worked on the movie, and needless to say, a lot has changed. I'd still jump at the chance to do more extra work for the set experience and the stories I can share here, but lately I've been focusing way more on getting my friends together, getting some lights and microphones and (as Joel Coen put it so wonderfully) playing in our corner of the sandbox. Should we ever find success, I like the idea of my appearance in 21 as the work of a spy in the studio machine. For now, though, I'm just glad I made my Nana proud.

It's a weird thing to look at yourself on the big screen. Yes, it turned out my mug was impossible to cut from 21 - I'm all over the place, specifically in the two classroom scenes that bookend the movie. And despite my fear of following in the footsteps of Pee-Wee, my friends and family assured me I did an excellent job of sitting, staring, taking notes and laughing at Kevin Spacey's terrible jokes. It's been a year since I worked on the movie, and needless to say, a lot has changed. I'd still jump at the chance to do more extra work for the set experience and the stories I can share here, but lately I've been focusing way more on getting my friends together, getting some lights and microphones and (as Joel Coen put it so wonderfully) playing in our corner of the sandbox. Should we ever find success, I like the idea of my appearance in 21 as the work of a spy in the studio machine. For now, though, I'm just glad I made my Nana proud.And make no mistake, 21 is every bit a product of that machine, calculated and predictable from beginning to end and engineered to appeal to a 14-year-old's materialism and horniness. It's pretty shallow, in other words, but also weirdly likeable - I could imagine it playing a triple feature with Hot Pursuit and Some Kind of Wonderful on "USA Up All Nite" one lazy Friday night in 1988. I know that's not the sort of recommendation that'll compel you to race to your nearest multiplex, but if you do see 21, make sure to keep an eye out for a brown-haired dude wearing a plaid shirt in the first classroom scene and a brown one in the second. That'd be me, a blogger and living easter egg.

Sunday, April 06, 2008

Thursday, April 03, 2008

Play the Game (4/3/08)

Tuesday, April 01, 2008

You try a stunt like that again and I'll braid your tits.

The following is my contribution to the 2nd Annual White Elephant Blog-a-Thon.

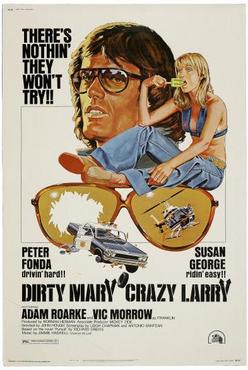

The following is my contribution to the 2nd Annual White Elephant Blog-a-Thon.Susan George is awesome in Dirty Mary Crazy Larry. We first see her lounging on a motel bed after a one-night stand with stock car driver turned criminal Larry (Peter Fonda) in a shot that (perhaps deliberately) recalls Faye Dunaway at the start of Bonnie and Clyde - she's tense, restless, looking for trouble. It's this urge for sensory gratification that is at the heart of the road movies that populated drive-ins in the '60s and '70s, promising high speed and vehicular mayhem with a fast, cool car driven by a free spirit set adrift on the open road. While Dirty Mary Crazy Larry doesn't have the potent existential kick of Vanishing Point or Two-Lane Blacktop (films that it pretty blatantly steals from), it does have a certain goofy charm. Like most of the films from John Hough, it has a meat-and-potatoes approach to its material, delivering on its modest promises - sometimes, a pretty girl in a fast car is enough.

Like Two-Lane Blacktop, Dirty Mary Crazy Larry is about a driver, his mechanic and the girl along for the ride. After robbing a grocery store, Larry and Deke's (Adam Roarke) getaway is complicated by Larry's most recent conquest, who repeatedly manipulates her way into going along for the ride. The first half of the movie makes clear what Quentin Tarantino was going for with Death Proof - there's little action, with most of the scenes focused on the tension between Larry (who constantly mocks Mary for being a chick) and Mary (who acts disgusted with Larry but goes along for the ride anyway). Much of this may be meant to pad the movie to feature length, but it's also an interesting little time capsule of gender relations in 1974. While I don't think Hough meant Dirty Mary Crazy Larry as a feminist statement, it's fun to watch a '60s icon (embodying the casual misogyny of the peace-and-love generation) meet his match in an unapologetically carnal '70s woman (recall the introduction of George, defiantly braless, in Straw Dogs). That gender politics made their way into a straightforward B-picture may or may not be representative of the paradigm shift happening at the time (certainly, tough-talking women existed in cinema before women's lib); either way, though, I imagine it at least gave the ladies who'd been dragged to the film by their boyfriends and husbands something to laugh at.

For any of its superficial nonconformist iconography, however, Dirty Mary Crazy Larry is squarely a product of the establishment. Consider the character of Captain Franklin (Vic Morrow), an old-school lawman determined to catch Mary, Larry and Deke. Morrow was a pro at playing grizzled, miserable bastards, and Franklin could be the perfect foil for the protagonists. Except that the film makes the odd choice of making Franklin a different kind of antihero, rebelling against bueracracy and modernity (he hates computers) in his obsessive pursuit of the trio. By making Franklin and Larry two sides of the same coin - both raging against the tide of change - the movie never approaches the radicalism of its predecessors. In a sense, it anticipates the mainstream co-opting of a very independent subgenre, with Morrow's Franklin only a few evolutionary steps away from Buford T. Justice.

The most important thing, though, is the car chases, and on this definitely delivers. The film's second half is an almost nonstop chase that delivers on the tagline's promise of "PETER FONDA drivin' hard!!" Watching Larry's Dodge Charger evade cop cars and even a chopper, it's hard not to be filled with the basic, childish glee of seeing the bad guys get away. Dirty Mary Crazy Larry is fast-paced, unpretentious fun, at least until its final minute. Looking around the internet, I see that the ending is quite admired for its unpredictability, but I was frankly thinking "wouldn't it be funny if - " when it happened. It's too much of an attempt to match the bleakness of Vanishing Point and Easy Rider, except that grafted onto a pretty light-hearted film, it's just hilariously arbitrary. As poetry Dirty Mary Crazy Larry leaves a lot to be desired, but it's pretty damn good pulp.