Is it possible to write about Watchmen the movie without comparing it against Watchmen the book? Almost every review of the film eventually devolves into a checklist of how plot points, characters, production design - indeed, every shot - recreate or deviate from Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' masterpiece. Every devoted fan of the book is going to have a detail or beat they sorely missed (I missed the Hooded Justice, after preventing Sally Jupiter's rape, teling her to cover herself up). To be fair, director Zack Snyder invites this kind of scrutiny; his film is as driven by an obsessive fidelity to its source material as his adaptation of Frank Miller's 300. I hated 300 for its monotonous visual style and seeming anti-intellectualism, and feared that Snyder was the worst possible choice for Watchmen, a comic driven more by ideological conflict than epic battles. During the stunning opening credits sequence, which presents an alternate history of the 20th century populated by superheroes scored to Dylan's "The Times They Are a-Changin'", I realized my fears were unfounded - Watchmen is every bit as ironic, complex and subversive as the book.

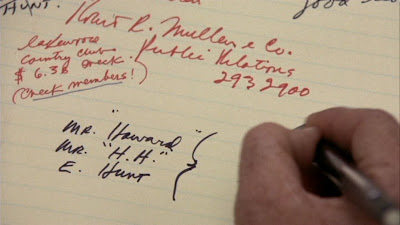

Is it possible to write about Watchmen the movie without comparing it against Watchmen the book? Almost every review of the film eventually devolves into a checklist of how plot points, characters, production design - indeed, every shot - recreate or deviate from Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' masterpiece. Every devoted fan of the book is going to have a detail or beat they sorely missed (I missed the Hooded Justice, after preventing Sally Jupiter's rape, teling her to cover herself up). To be fair, director Zack Snyder invites this kind of scrutiny; his film is as driven by an obsessive fidelity to its source material as his adaptation of Frank Miller's 300. I hated 300 for its monotonous visual style and seeming anti-intellectualism, and feared that Snyder was the worst possible choice for Watchmen, a comic driven more by ideological conflict than epic battles. During the stunning opening credits sequence, which presents an alternate history of the 20th century populated by superheroes scored to Dylan's "The Times They Are a-Changin'", I realized my fears were unfounded - Watchmen is every bit as ironic, complex and subversive as the book.Starting with a balletic fight between retired superhero Edward Blake, AKA the Comedian (Jeffrey Dean Morgan) and a mysterious intruder that ends with Blake's murder, Watchmen takes place in an alternate 1985 where the existence of superheroes has resulted in, among other things, a U.S. victory in Vietnam, Nixon's fifth term in office and the impending threat of nuclear war. With superheroes having been outlawed a few years earlier, the costumed crimefighters have either retired or agreed (like the Comedian) to work for the government; only Rorschach (Jackie Earle Hailey) a masked vigilante (described as a "nutcase" by Moore) driven by vengeance and a black-and-white moral code. Rorschach's investigation of Blake's murder leads us into the stories of his fellow crimefighters and their forefathers (dubbed the Minutemen) and the world they live in. The film is a triumph of design; working with production designer Alex McDowell (whose credits include Fight Club and Minority Report), Snyder has created an alternate 1985 that serves as a funhouse mirror of the real 1985, pop cultural signifiers from the decade and artistic influences that informed the book. As I'm a sucker for movies that blur the line between actual and pop cultural history, it's the little details - the Ridley Scott-inspired tv commercials, the Man Who Fell to Earth-inspired wallpaper in the apartment of atom-age demigod Dr. Manhattan (Billy Crudup), the Muzak version of "Everybody Wants to Rule the World" playing in the tres sheik offices of billionaire mogul and "smartest man alive" Adrian Veidt, aka Ozymandias (Matthew Goode) - that bring the film's universe to life.

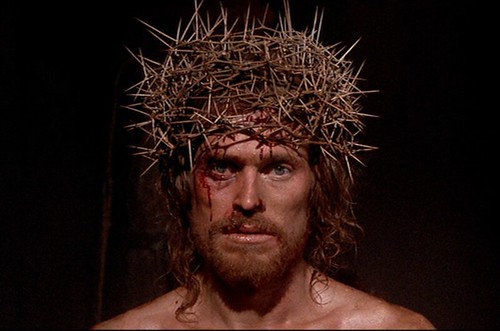

The structure of both the book and the film digresses from the murder mystery plot to flesh out the stories of each of the crimefighters, allowing for an understanding of the personal and philsophical reasons behind each characters' decision to become a masked vigilante even as each new story reveals the limitations of the previous crimefighter's ideology. My favorite character has always been Dr. Manhattan - the film thankfully retains the graphic novel's most powerful sequence (scored to Philip Glass' "Pruit Igoe/Prophecies"), as Manhattan, formerly Dr. Jon Osterman, recalls from his hideaway on Mars how, after an accidental atomization, he was transformed into a "quantum super-hero" whose understanding and control of the physical properties of the universe grow in proportion to his detachment from humanity (insert obligatory reference to glowing blue penis). I was surprised, watching the film, to find a deeper appreciation for Rorschach, a absolutist nutter who nevertheless is more aware of his own shortcomings than any of his fellow crimefighters. This is partly due to the performance by Haley, who succeeded with Little Children in making a pedophile sympathetic and, even though most of his performance is delivered through a mask, is the most compelling performer onscreen in any scene he appears in. The rest of the cast has varying degrees of success - Crudup is unexpectedly but effectively low-key as Dr. Manhattan, Morgan is darkly hilarious as the Comedian, and Patrick Wilson is great as Dan Drieberg, an insecure middle-aged guy, formerly known as Night Owl, who can only get it up after rescuing innocents. Malin Akerman, as Manhattan's girlfriend and second-generation crimefighter Silk Spectre, is alright in an underwritten role (Carla Gugino, as the first Silk Spectre, fares better). Matthew Goode is a visually striking choice for the brilliant and powerful Ozymandias, and the emotional detachment he brings to the role (along with the strange accents) are reminiscent of Thomas Jerome Newton.

It's Ozymandias' part of the film, however, that is slightly lost in translation. I don't mind the change that Snyder and screenwriters David Hayter and Alex Tse make to the film's ending - one deus-ex-machina is as good as another, and this one actually makes more thematic sense. But the surgery performed on the narrative to make the change results in a final twenty minutes that feel slightly truncated and off-balance compared to the rest of the film, and I winced when a famous line spoken by one character was omitted and then recalled, out of nowhere, by another. This misstep, however, only serves to illustrate what makes the rest of the film so unique - other than Ghost World, I've never seen another comic book adaptation so committed to the idiosyncrasies of its source material. While its relative commercial failure was probably inevitable - the audience I saw it with was palpably thown off during the rape scene and, by the ending, was completely lost - this only increases my affection for the film. Whether you love or hate Watchmen, it's one of the most admirable examples of a big-budget filmmaker putting one over on unsuspecting audiences; a friend and I continued to debate the actions of the characters for days after seeing it, and I hope some of those who were thrown off guard were inspired to do the same instead of completely dismissing the film. While it remains to be seen whether Snyder is just a master of absorbing his source material or if, as Watchmen suggests, he may be more than a slick visual director, remains to be seen; for now, however, the question is beside the point. The first time I saw Watchmen I was overthinking it, measuring it against the movie I've had in my head since I first read the book. The second time, experiencing the movie as its own thing, I realized how weird and dark and awesome it truly is. Alan Moore would do well to lift his curse.

Happy new year, everyone!

Happy new year, everyone!