Viewing Nosferatu in the darkened cave of the Brattle, I was reminded of Henry Fuseli's painting The Nightmare. The goblin-like figure, who has taken and destroyed the beautiful woman, inspires both pity and repulsion. Yet the title also suggests that the monster is the woman's own creation; beauty and beast are inextricably linked in the nightmare cycle. Count Orlok (Max Schreck) inspires the same mixed emotions. A professor of semantics from BU argued after the film that Schrek's evil stems from his only possessing love of self, rather than love of God or of the world. Yet who amongst us has never acted out of self-gratification with unfortunate results?

The plot, well-known from countless versions of Stoker's Dracula but first filmed here, follows Hutter (Gustav von Wagenheim), a broker who travels to Orlok's castle in the Carpathian Mountains. Orlok intends to buy a home in Bremen, but when he sees a picture of Hutter's wife Ellen (Greta Schroder), he is overcome with desire. Orlok imprisons Hutter and travels aboard a ship to Germany, bringing a strange plague with him. As with most silent films, the plot is by necessity secondary to the images themselves, which achieve a singularly otherwordly atmosphere; Murnau's film feels like a waking nightmare.

The filmmaking on display here is remarkable, particularly for its time; when most films were static and uncomplicated, Murnau's film is filled with odd uncomfortable angles, and the camera is often in fluid motion. This is a horror film from before such genre distinctions were cemented, and its influence on countless filmmakers to come is evident in almost every frame. The interplay of shadow and light alone make for a definitive study of the genre. But if the main virtue of Murnau's film were its importance, than it would be a chore to watch. Instead, it remains a haunting, grandly entertaining "Boo!" movie.

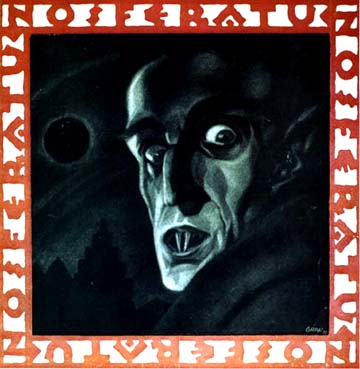

The key is Max Schreck. A bit player before Murnau discovered him, Schreck is frighteningly believable as Orlok (of course, Shadow of the Vampire brilliantly played off of his verisimilitude). This is partly due to the crude but effective makeup job - the protruding canines, clawed hands and skeletal frame which Herzog and Kinski smartly chose to recreate in their remake. But Schreck also inhabits the vampire with a soulfulness that is both otherworldly and human. When he consumes a victim, there is little aggression in his manner; he almost appears to be nursing. There's a weird innocence to his crooked smile as he emerges from a coffin; his creeping walk is made more unnerving by the vacant look in his eyes. In The Nightmare, where the creature's fearsome appearance is offset by his diminutive size; similarly, Orlok is both monster and child, and it would be possible to say he deires Ellen as a lover, mother, food, or all of the above.

Ellen gives herself to the monster, and the audience at the Brattle had differing interpretations of her motives. Some saw it as a pure act of self-sacrifice, coaxing Orlok into sunlight to spare the village from the plague. Others saw it in more erotic terms, and Murnau certainly gives us visual clues earlier to support this claim. But whether or not Ellen wishes to be seduced, Orlok does not assume the role of seducer that other actors, from Bela Lugosi to Gary Oldman, would in the Dracula role. Note how little Orlok struggles against his eventual fate; one could chalk this up to awkward staging, but I prefer to think that his relative indifference to his own survival is exactly the point. It can't be much fun going through life doomed to consume everything you find beautiful; watching Nosferatu, I found myself wondering about the ways in which we doom ourselves to the same fate.

No comments:

Post a Comment