Full Metal Jacket opens, as the twangy "Hello Vietnam" plays on the soundtrack, with a montage of Marine Corps recruits getting buzzcuts. We examine one bored, distracted face after another until the sequence ends with a shot of the piles of hair collecting on the linoleum floor. Their individuality has been stripped away, and the first half of the film is concerned with the military's methods of rebuilding these "unorganized, grabastic pieces of amphibian shit" into a powerful, violent collective. Stanley Kubrick exerts a similar control over his most restrained, calculated film; as with any of his films, it's fascinating to consider how the ideas that drive Full Metal Jacket are mirrored in the director's process.

We follow a platoon of recruits during their training at Paris Island under the delightfully profane Gunnery Sergeant Hartman (R. Lee Ermey). Both the film and Ermey have earned their place in the pop culture firmament, of course, thanks to the character's endlessly quotable dialogue. But to recall Hartman simply as a collection of one-liners is to underestimate Ermey's brilliant performance. A retired Staff Sargeant and Vietnam vet, Ermey lends the film enormous verisimilitude and helps to steer Hartman clear of becoming a cardboard, Strother Martin-like caricature. Ermey was one of the rare actors that Kubrick allowed room to improvise, and his torrents of almost poetic verbal abuse not only lend the film credibility, but also color in shades of ambiguity. On the one hand, we're invited to recoil at Hartman's dehumanizing treatment of the recruits, particularly the dim, sensitive Private Leonard Lawrence (Vincent D'Onofrio), who is dubbed "Private Gomer Pyle." On the other hand, you can sense both Ermey's pride in the role and Kubrick's respect for the character; Hartman is never depicted simply as a sadist, but as a man who is preparing these "maggots" to serve in his beloved Corps. It is a sign of Kubrick's faith in the audience's intelligence that he allows us to answer the question of whether such treatment is necessary for ourselves.

Full Metal Jacket spends a great deal of time establishing the monotonous routines of basic training ("1, 2, 3, 4, United States Marine Corps!"), and it's no wonder that Kubrick, who would put his actors through the paces with dozens of takes, would be drawn to the methodical aspect of the military experience. The man who made Shelley Duvall cry invites us to consider the morality of pushing characters like Private Pyle to the breaking point because they don't fit into a well-oiled machine ("Everything clean"). Our narrator, Private Joker (Matthew Modine), is assigned to whip Pyle into shape, and we share both his compassion for and impatience with poor Pyle. A scene where the recruits give Pyle a brutal beating to teach him a lesson is painful to watch, but rather than going for easy emotional manipulation by allowing us to view the scene from Pyle's perspective, Kubrick shoots the scene from Joker's point of view as he attempts to drown out Pyle's childlike sobs. We share Joker's (and Kubrick's) anger at Pyle's lack of restraint, and so we are partially implicated in Pyle's "major malfunction."

The second half of the film alienates much of the audience, and it is indeed an abrupt tonal shift from Paris Island. Nancy Sinatra announces this shift on the soundtrack; country has given way to rock and roll. Joker (Matthew Modine), now a combat journalist, hooks up with fellow Parris Island graduate Private Cowboy (Arliss Howard) near Hue. These scenes, particulary the "Vietnam: The Movie" sequence, are often dismissed as aimless, but they actually serve as a thorough demythologization of war. John Wayne is frequently name-dropped, but the closest thing we get to John Wayne is Animal Mother (Adam Baldwin), a dull, racist meathead. These kids are armed only with their rifles and well-worn cliches about camaraderie and valor learned from movies. Animal Mother's idiocy allows him to inadvertently see the war as it is; when he remarks that if he were to die for a word, that word would be "poontang," at least he chooses something tangible. Ever the pragmatist, Kubrick largely sidesteps political philosophy and depicts Vietnam as the place we sent a lot of well-meaning, naive kids to die.

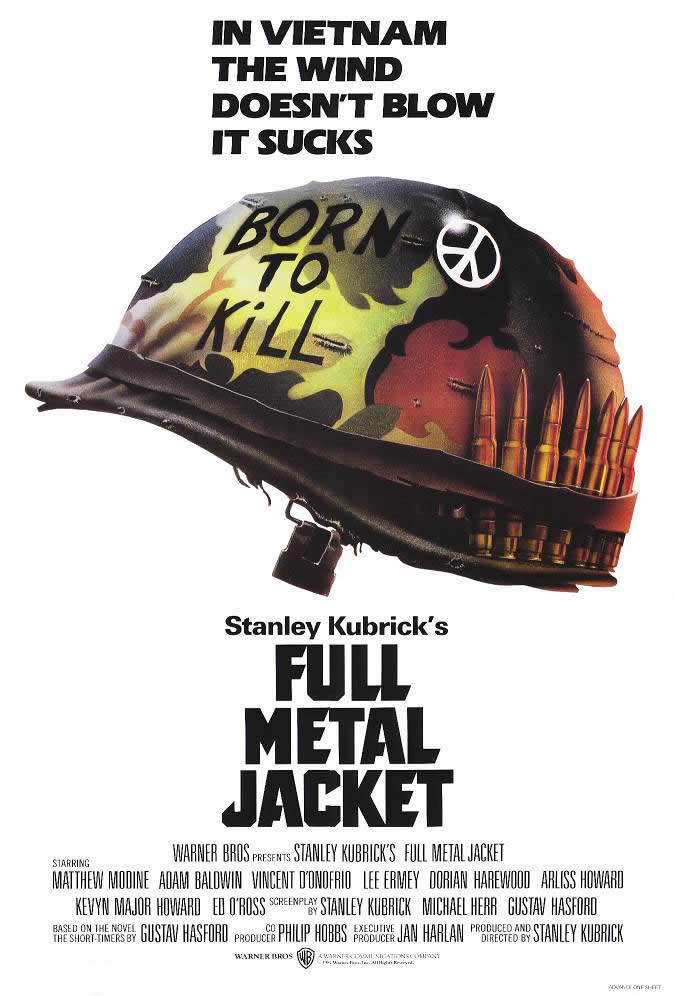

Kubrick's clinical approach turns chilling in the final scenes, as a sniper offs several troops. Each death is accompanied by a hollow blast on the soundtrack that echoes the film's icy electronic score (composed by Kubrick's daughter, Vivian). The director is a master of irony, using it not as a cheap, sarcastic tool but as a microscope that exposes underlying truths; here, the well-oiled military machine is severely crippled by one resorceful individual. It's enough to turn Private Joker, who wears a peace symbol and a helmet reading "BORN TO KILL," from a detached outsider to a "hardcore" killer. The war/sex parallel seen throughout the film and previously in Dr. Strangelove comes into focus here, as Joker is "born again hard." He's a walking erection, and rather than editorializing, Kubrick leaves us to decide whether this is evolution or regression. As the soldiers march into the darkness singing the Mickey Mouse Club theme song, we reflect on their homecoming, when they will return to Mickey's world, maybe for the better, maybe for the worse, but definitely not the same.

No comments:

Post a Comment