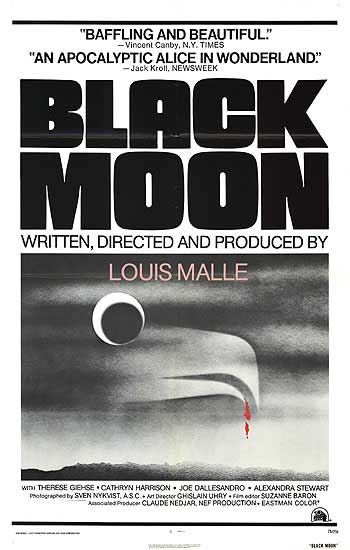

Black Moon alludes heavily to Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, which makes perfect sense; Lewis Carroll's books are progenitors of a long line of absurdist works, and Louis Malle's film succeeds in this tradition. And while Black Moon is a strange, elusive and haunting success in its own right, it is even more impressive when placed in the context of Malle's other work, which is characterized by precise insight into the human condition but remains firmly rooted in a world that is recognizably our own. Here, Malle takes his recurring themes and concerns and disappears down a rabbit hole; the result is a brilliant realization of the uncanny.

Lily (Cathryn Harrison) is a teenage girl roaming through an overcast countryside; civilization has collapsed (or is perhaps yet to begin), and gas-masked men summarily execute women on sight. After conversing with some insects, Lily escapes to an isolated farmhouse where she meets a bedridden elderly woman (Thérèse Giehse) who talks into a two-way radio connected to the infinite when she isn't conversing in an unknown language with a rat named Humphrey. Also coming and going are a mute young man (Joe Dallesandro) and his sister (Alexandra Stewart), who is cruel to Lily for unknown reasons and who provides the old woman with a puzzling form of nourishment. Characters die and are born again, a gang of naked feral children herd pigs, and a unicorn appears out of thin air to mock Lily's assumptions about the world she finds herself in. The proceedings are delibrately strange, but Malle uses the Alice connection to provide us with the foundation for a frame of reference. But Black Moon's most drastic departure from its source is its lack of a clear delineation between reality and fantasy; the world that Lily escapes may or may not be our own, the farm may be a microcosm of that larger world, and each world constantly threatens to collapse upon the other. The old lady and the unicorn each deny the other's existance, but Malle gives no clue as to whether either or both are telling the truth; by avoiding a binary opposition between the real and the unreal, Malle opens his film up to a whole other realm of tantalizing possibilities.

There's an argument to be made for a Freudian reading of the film, as Lily is frequently mocked for her emerging sexuality - her panties have a habit of falling down no matter how hard she tries to keep them on, the young man's horny gaze is repeatedly equated with violence, and snakes have a tendency to pop out of unexpected places. But Malle is not bound by a strictly analagous reading of his film (note the absence of a father figure), allowing characters to contradict one another and the laws of the film's reality to constantly shift. Black Moon can be handily read, like Malle's later film Pretty Baby, as the story of a young woman's resistance to her inevitable induction into a phallocentric world (making the Alice connection, given Carroll's sexual proclivities, tantalizingly kinky). But more broadly, it's about the disconnect from the world around us that we feel at moments of personal (and societal) transition - adolescence, for one, but also aging, death and rebirth. Lily ultimately gives herself to the old woman in a way that suggests her acceptance of this constant state of uncertainty; Malle smartly denies us an easy summation of the film's meaning, but he does leave us with the suggestion that for Lily, at least, real understanding is at least a bit more attainable.

Black Moon was shot by Sven Nykvist, Ingmar Bergman's frequent collaborator, and he films the rural settings in a way that makes them remarkably tactile (this is partly why I prefer the film to Godard's Weekend, an intelligent film set in a similar world that sacrifices our engagement for self-satisfied trickery). Nykvist's work is reflected in the strategy of the entire film, which presents its fantastic characters and situations matter-of-factly; by using literal narrative methods (hard cuts, natural light), Malle makes his unicorns and talking animals all the more disturbing for their complete lack of artifice. The sound design is brilliant as well, creating a disconnect between what we see and what we hear (a slug crawling across a log has the volume of a tank rolling along a hill). By constantly playing with our perspective, Malle forces us to consider the value we place in our own assumptions about the nature of the world around us. The result is a mesmerizing sensory experience that would make Lewis Carroll proud; as the author himself once admonished, "Be what you would seem to be - or, if you'd like it put more simply - never imagine yourself not to be otherwise than what it might appear to others that what you were or might have been was not otherwise than what you had been would have appeared to them to be otherwise."

3 comments:

I taped this a few months back; glad to see it's worth a watch.

It can't work in actual fact, that's what I think.

Actually I didn't like the film, it bores me to hell, any other recommendation?

Post a Comment