My favorite Bob Dylan album is a toss-up between Blonde on Blonde and Blood on the Tracks; ask me for my favorite on a particularly perverse day, however, and I might say Self Portrait, Dylan's critically reviled 1970 attempt to torpedo his own iconic status. It's virtually unlistenable, perhaps intentionally so, but on a conceptual level it's fascinating, serving as a sort of Rosetta stone for Dylan. At the center of the album (and all of Dylan's music) is the paradox of the artist who will do anything, even self-destruct, to conceal his true self - a self that, no matter how metaphors the artist uses to bury it, remains totally naked and self-evident to anyone listening. This paradox is also at the heart of I'm Not There - that is, if it's even accurate to say that Todd Haynes' radical biopic has any center at all. As shape-shifting and elusive as its subject, Haynes' film (once subtitled Suppositions on a Film Concerning Bob Dylan) doesn't just sidestep the conventions of the subgenre, it completely demolishes them. What emerges is a representational, almost abstract interpretation of Dylan's life and work in which biographical details, lyrics, names and cultural artifacts are woven into a complex tapestry. If this sounds like a dry intellectual exercise, it is; that said, the more times I've seen the film, the more its metatextual structure reveals unexpected pleasures. You don't have to be an expert in Foucault for I'm Not There to rock your socks off.

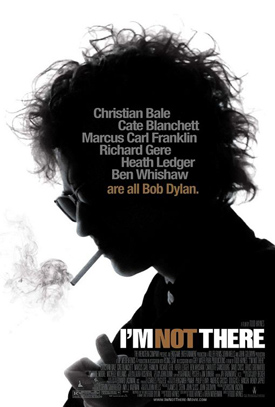

The marketing for I'm Not There centered around the seeming stunt casting of six actors playing Bob Dylan. But the film itself is deeper than Solondz-esque gimmickry, revolving around not only six different actors but six different characters embodying or suggesting different aspects of Dylan's multifaceted persona. We're first introduced to Woody Guthrie (Marcus Carl Franklin), a 12-year-old black guitarist who sings songs about unionization in 1959 before being advised to live his own time. This advice leads directly to earnest folk singer Jack Rollins (Christian Bale); who is followed onstage by leather-clad provocateur Jude Quinn (Cate Blanchett). There is also Robbie Clark (Heath Ledger), an actor who once played Rollins, and Arthur Rimbaud (Ben Wishaw), who is seen only in an interview (or perhaps a deposition). And then there is Billy the Kid (Richard Gere), who we'll get back to in a minute. Taken on their own, any of these segments would make a fascinating interpretation of Dylan's life in miniature, their respective protagonists brushing up against moments both iconic and rumored. Taken as a whole, Haynes' dense, challenging narrative (co-written by Oren Moverman) portrays Dylan in a manner worthy of the singer's Cubist method - as Dylan himself once explained (and is quoted in the film), "You've got yesterday, today and tomorrow all in the same room, and there's very little you can't imagine not happening."

The marketing for I'm Not There centered around the seeming stunt casting of six actors playing Bob Dylan. But the film itself is deeper than Solondz-esque gimmickry, revolving around not only six different actors but six different characters embodying or suggesting different aspects of Dylan's multifaceted persona. We're first introduced to Woody Guthrie (Marcus Carl Franklin), a 12-year-old black guitarist who sings songs about unionization in 1959 before being advised to live his own time. This advice leads directly to earnest folk singer Jack Rollins (Christian Bale); who is followed onstage by leather-clad provocateur Jude Quinn (Cate Blanchett). There is also Robbie Clark (Heath Ledger), an actor who once played Rollins, and Arthur Rimbaud (Ben Wishaw), who is seen only in an interview (or perhaps a deposition). And then there is Billy the Kid (Richard Gere), who we'll get back to in a minute. Taken on their own, any of these segments would make a fascinating interpretation of Dylan's life in miniature, their respective protagonists brushing up against moments both iconic and rumored. Taken as a whole, Haynes' dense, challenging narrative (co-written by Oren Moverman) portrays Dylan in a manner worthy of the singer's Cubist method - as Dylan himself once explained (and is quoted in the film), "You've got yesterday, today and tomorrow all in the same room, and there's very little you can't imagine not happening."

The of such a fragmentary approach is total, self-indulgent disaster that would make Renaldo and Clara look like Walk the Line. That the film's risks succeed so admirably is largely thanks to the cast, who breathe life into Haynes' signifiers. The best is Cate Blanchett, admittedly given an advantage as she's playing Dylan in his folk-killing, wine-swigging, chain-smoking, condescending asshole phase (possibly the coolest anyone has ever been, ever). But Blanchett's Jude Quinn, like her Katharine Hepburn, is more than an uncanny impersonation, finding previously unexplored shades of vulnerability, even fatalism in Dylan's Don't Look Back-era swagger, and the gender-bending casting is a nod to Dylan's androgynous appeal. Less iconic but also wonderful are Bale as the wide-eyed but increasingly world-weary young folkie, and Ledger, evoking Blood on the Tracks as a performer in existential crisis during the breakup of his marriage to wide-eyed Claire (Charlotte Gainsburg, heartbreaking here playing, as Bale did in Velvet Goldmine, our doorway into the narrative).

The performances are held together by Haynes' bold representational approach, which anyone who has seen Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, Far From Heaven or the way underrated Velvet Goldmine will recognize immediately. Here, his semiotic games are looser and more playful than in the past - beyond intellectualizing his subject, Haynes' grasp of synchronicity creates an experience not unlike getting lost in a favorite album. When Haynes opens a certain performance of "Maggie's Farm" with Jude and the band opening fire on the audience, no matter what you think about Dylan going electric (I think Pete Seeger is a tool), you can't help but be delighted at the film's structural and aesthetic abandon. The entire movie is similarly dizzying, with not only cameos for the decade's other iconic figures - I'm partial to David Cross as Allan Ginsburg - but a cascade of images and ideas taken from a host of other cinematic and pop cultural sources (brought to life with astounding verisimilitude by DP Edward Lachman). There's the cinema verite of Don't Look Back and the talking-head approach of No Direction Home, but also loving nods to Fellini, Richard Lester, The Graduate and many more cultural touchstones. This goes deeper than nostalgia, deeper than a cynical greatest-hits collection for baby boomers; the cumulative effect is a singular portrait of the symbiotic relationship between the artist, his work and the zeitgeist into which they are born.

Haynes' most audacious move, the one I was sure would be totally ridiculous, is having Richard Gere play an aging Billy the Kid wandering through a beautiful, barren Western landscape existing in a completely different world from the film's. But, more than a loving Peckinpah homage, the Billy the Kid sequences are remarkably moving; returning to them again and again when I think about the film, their seeming inscrutability comes into focus. Gere's Billy is Dylan as pure embodiment of his music - separated from politics, from anything contemporary, his symbols become representative of nothing except the greater chain of human experience, truly existing out of time and, therefore, eternal. An elegy for artists made immortal by the work they leave beind (how sad, how perfect, that the lyrics of its title song could be referring to its costar's untimely passing), I'm Not There is a triumph of art for art's sake and a leading witness in the trial of infinity.

3 comments:

Thanks so much for your article, quite helpful material.

Well, I do not actually believe it is likely to have success.

you really kind of like getting blasted out of your skin??? wow that is a little peculiar to me, but every ones the right to like anything that person wants

Post a Comment