Why do we value our favorite things? Why do we even take the time to designate favorites? What does our relationship with the artworks that most profoundly move us say about who we are? My favorite song is "Tangled Up in Blue," my favorite book is Franny and Zooey, and now, my favorite film is Blue Velvet. The film was comfortably residing in the bottom half of my top ten until a few weeks ago, when something was irrevocably shaken. As Bruce Willis' character in 12 Monkeys points out, the film remains the same - we're the ones that change.

"She wore blue velvet/Bluer than velvet was the night/Softer than satin was the light/From the stars"

The song "Blue Velvet" describes a haunting, fleeting romance that has now been lost; Bobby Vinton's voice aches as he sings about the velvet he can still see through his tears. The song is deceptively simple, and it forms a perfect marriage with the opening sequence of David Lynch's film. Tranquil images of suburbia give way to a startling moment of violence (Jeffrey's father clutching his neck and dropping to the ground) and a hidden layer of chaos (the insects attacking each other right under our noses). It's easy to read these early moments as a declaration of our world's fundamental savagery and the ways we sweep our indescretions under throwrugs lovingly purchased at Linens 'n' Things. But it's more than an attack on the American dream; it's also an affirmation of the power and importance of such dreams. Lumberton is a world where light and dark coexist, and Blue Velvet is about the collision of these two opposing forces in Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan), who is either "a detective or a pervert." Or maybe both.

Jeffrey is a college student who has returned to Lumberton, his hometown, because his father is ailing. One day, walking home from the hospital, he discovers a human ear lying in a field. After reporting it to the police, he and a detective's teenage daughter, Sandy Williams (Laura Dern), begin their own Nancy Drew-esque investigation. This leads them to Dorothy Valens (Isabella Rossellini), a mysterious chanteuse. Dorothy's son and husband are being held captive by Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper), a gas-sniffing monster who has trapped Dorothy in a violent, perverse, sadomasochistic relationship. Through the course of the film, Jeffrey veers between Sandy, who dreams of robins that spread love throughout the world, and Dorothy, who describes sex as a disease. While this description may make Blue Velvet's sexual politics sound binary and simplistic, to view the film is to realize that Lynch's message is anything but simple.

See my breast? You can feel it. My nipple. Still hard. You can touch it. You can feel it. Do you like the way I feel?

Yes.

Feel me. Hit me.

The first third of Blue Velvet establishes an offbeat yet reassuringly familiar and comic environment. We're invited to laugh with Jeffrey and Sandy as they stumble along on their amateur sleuth work. The kids have a cute chemistry; perhaps, we think, they'll kiss in the last reel. Then Jeffrey decides to spy on Dorothy from her closet, and Blue Velvet suddenly flies violently off the rails. It's frankly a marvel that the film works at all; the scene in Dorothy's apartment rips us from our comfort areas and drags us into the darkest areas of human emotion via raw, lurid sexuality. We are first, through Jeffrey, confronted with our own voyeuristic intentions. When Dorothy asks Jeffrey if he likes to watch women undress, she is asking us as well. As Jeffrey is forced to strip and engage in a sex act that is as arousing as it is terrifying, we have no choice but to acknowledge the same conflict between desire and fear in ourselves. With Frank's entrance, identification gives way to something at once alien and familiar - Hopper is terrifying in the role because he is at once utterly evil and heartbreakingly human. And funny too - our apprehension at the brutal near-rape at the center of the film is undercut by our awareness of Frank's utter ridiculousness. Each punch to Dorothy's face, each cry of "Don't you fucking look at me!" is charged with horror and eroticism, dread but also a perverse curiosity, as well as the nagging question of whether this is all a joke. Frank leaves, and Jeffrey is left to cradle Dorothy, who offers herself to him in a way that is wrenchingly needy. Her red, ripe lips fill the frame, begging us to hurt her as though nothing would be more pleasurable. Even the squarest cat in the audience would have to concede that this is intriguing and sort of hot. In about ten minutes of running time, Blue Velvet delivers on the promise of its opening sequence, pulling back the reassuring mask of indie quirk to reveal something darker and infinitely more complicated. Lynch excells at this sort of switch, and many of his imitators have failed to repeat his magic; they copy the weirdness without finding the soul within.

I'm seeing something that was always hidden. I'm involved in a mystery. I'm in the middle of a mystery and it's all secret.

You like mysteries all that much?

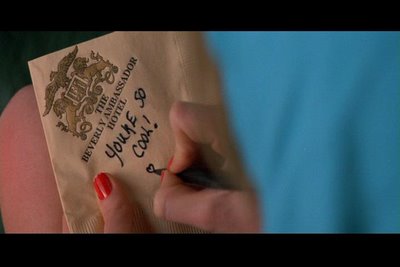

Yeah. You're a mystery. I like you very, very much.

The crime plot in Blue Velvet is incidental. It serves a functional purpose in bringing the characters together, and as we only know what Jeffrey knows (very little), it serves to remind us that there is so much beyond our frame of reference. The mysteries Jeffrey is pursuing are the mysteries of love referenced on the soundtrack; all of the main characters are driven by romantic longing in one way or another. Sandy is an innocent attracted to Jeffrey's perversion and capacity for cruelty (note the subtle moments when he manipulates the younger girl into giving him what he wants). Jeffrey, in turn, idealizes Sandy; she's the wide-eyed girl that he can take home to mom and dad. Lynch reserves the heart of the film for Sandy, and Dern delivers the famous "robins" speech with perfection, underlining Sandy's optimism and quiet yearning. The speech moves Jeffrey, yet in the next scene, he's back at Dorothy's apartment, the two of them locked together like figures in a painting by Francis Bacon (Lynch's favorite artist). Sandy is the girl that Jeffrey dreams of; Dorothy is the woman he jacks off to. Lynch is treading on the borders of misogyny here, yet his message is more complex. Sandy has elements of darkness (why does she forgive Jeffrey so easily?) and Dorothy has light (she started everything, at least, to save her family). Lynch is exploring the ways that love can send people spiralling in dramatically different directions. Love can mean soft kisses while slow-dancing at a high school party, and it can also mean wandering naked, beaten and dazed through someone else's yard. Both are equally possible, and Lynch only reserves his indifference for those who are simply incapable of experiencing real emotion (the running joke of Sandy's dim, cardboard boyfriend underscores this point).

Lynch even has sympathy for his devil. When we see Frank at the Slow Club, clutching a square of Dorothy's bathrobe and silently weeping, we have to accept his humanity. Who is Frank? What happened to turn him this way? Was he just born damaged? Lynch has Jeffrey ask "Why are there people like Frank?" and later has Frank respond "We're the same." It's simple, but that doesn't make it untrue. The captivating joyride sequence, where we meet Frank's fey, "suave" friend Ben (Dean Stockwell), takes us even deeper into the labyrinth. Who the hell is Ben? Stockwell creates a fascinating enigma, a character that is apparently all surface and is capable of total indifference ("Here's to your fuck"). And yet when he lip-synchs to Roy Orbison's "In Dreams," Frank is visibly shaken. There's a power to artifice, and Lynch knows this; it's why we respond so strongly to fictional narratives even though there is no logical reason to do so. We long too - for romance, for strangeness, for kink, for adventure - and Lynch pulls that longing into unexpected places. The scene by the side of the road, where Frank repeats "In Dreams" to Jeffrey while showering him with kisses (because this movie needed homoeroticism, it just wasn't strange enough otherwise), lays bare the unabashed emotion - the love, the hate, the fear and wonder - that is at the heart of both Lynch's work and the whole bloody history of human experience.

"Sometimes the wind blows/And you and I/Float in love/And kiss forever/In darkness"

It's an oft-overlooked aspect of the Lynch canon that while he treads heavily in darkness, his films are ultimately very optimistic. Lost Highway is the only one that ends in a truly downbeat manner; Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, and Mulholland Drive all contain the promise of transcendence beyond this life; Dune, Wild at Heart, and The Straight Story all hint at the possibility of peace on earth. Blue Velvet is unique in that it preposes a reconciliation of light and darkness. The hero ultimately defeats the monster by confronting the darkness existing within him (would the Jeffrey we meet at the start of the film be capable of figuring out the radio bit?). Peace is wholly restored - we see families united, and the last image is of a mother holding her child before the camera tilts upwards to the sky. And yes, the robins return. And yes, famously, the image looks patently artificial. But no, it's not just a glib joke. It's a challenge - knowing what we know now, can we accept that which we see? But on the other hand, having touched darkness, doesn't that make the light all the more valuable?

I realize I'm becoming vague, and that is because the ending of Blue Velvet is something I've changed my mind about countless times - it's a giant question mark. And that's why I love it. I've come to recognize life as a mosaic of different feelings and experiences that clash and intertwine in both violent and lyrical ways. This film, more than any other, reflects life as I know it - scary and sexy and funny and elusive and beautiful. I hear Sandy tell me that "There's trouble 'till the robins come," and in my heart I know she's absolutely right. It's a strange world, isn't it?

Best. Movie. Ever.