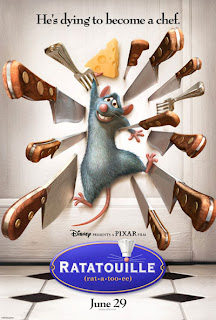

Ratatouille

Ratatouille takes place in the restaurant of a famous, deceased chef known for both his culinary innovations and his emphasis on accessiblity, with his motto "Anyone can cook!" In the chef's absence, small-minded vulture capitalists have co-opted his likeness and ideology for maximum profit, churning out cheap, microwavable bastardizations of his work. I found myself thinking about Walt Disney's legacy during

Ratatouille, similarly commodified and cheapened over recent years (not that the guy was a saint, but that's beside the point). Disney's saving grace has been their relationship with Pixar, a company with a deep, prodigious grasp of both animation and storytelling that seems dedicated to preserving everything that fodder like

Brother Bear Goes Bananas aims to destroy. This is a company that can understand the story of an ambitious little rat who surreptitiously assumes the role of an interspecies cultural attache;

Ratatouille's makers know what it's like to be the little guy, armed only with impeccable taste.

The rat in question is Remy (Patton Oswalt), who spends his days with his extended family picking through compost piles. While his father Django (Brian Dennehy) and his brother Emile (Peter Sohn) are content scarfing down junk for sustenance, Remy regards food as an art form. Inspired by the imaginary apperance of his hero, the late chef Gusteau (Brad Garrett), Remy finds himself hiding in Gusteau's restaurant, now struggling to stay afloat thanks to a vicious review by critic Anton Ego (Peter O'Toole). After a series of wacky misunderstandings (I love writing that), Remy is secretly puppeting a clumsy garbage boy named Linguini (Lou Romano). But the plot isn't the main thing - like Bird's other features, Ratatouille is unusual for a cartoon in that it is decidedly character driven. A film that is largely about taste, Ratatouille is as much about personal moments - the delightful visualization of the emotional experience of eating is a high point - as it is about kiddie-film noise. One of the most impressive things about Pixar is its willingness to go small - even an superhero movie like Bird's The Incredibles is at heart a character study. It's refreshing to find a studio that has that sort of faith in pure story, and in the intelligence of its audience.

This sense of intimacy extends to the design of the film. Movies set in France usually rely heavily on repeated shots of the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre, and baguettes; while Ratatouille's Paris is a digital simulacrum, it somehow evokes the real thing better than many films shot in Paris (certainly better than the suprisingly poor Paris, je t'aime). By giving us a rat's-eye view of the city, Bird and the animators capture a detailed, subjective version of Paris that becomes as tangible as Venice in Don't Look Now. One gets a real sense of the city's cultural history, which gives the lighthearted film an unexpected emotional resonance - Ratatouille is a celebration of taste, not just for food but for any form of creative expression (or appreciation; rarely has a film so loved its audience). Thankfully, Pixar's taste is impeccable, and they spare us poorly cast superstar voices, continuing to cast in delightfully unxpected ways (standouts here are Oswalt, Janeane Garofalo as a fierce sous chef, and O'Toole relishing every quintessentially British putdown). No already-dated pop cultural references, smarmy innuendo or Smash Mouth either; the humor here is smart and understated. And best of all, Ratatouille never condescends to its largely young audience, assuming, as the best children's movies do, that kids are capable of getting the joke.

Ratatouille is a fun, sweet movie, and yet I also found it weirdly inspiring. Its simple, wonderful message - that a life devoted to sharing one's appreciation of culture can help make the world a better place - encouraged me deeply on a particularly discouraging day. It's a great message for kids, urging them gently to chase their passions, and it's delivered with a perfect light touch. The ending of the film reminds of Pixar's assumption of creative control at Disney, the little guy now in control of the giant machine. If Ratatouille is any indication, they're just the right people to restore the Magic Kingdom to its former glory. Mouse, meet rat.