The following was written as a contribution to the Vampire Blog-a-Thon hosted by Nathaniel R. at Film Experience Blog. Check it out for more Halloween goodies.

The following was written as a contribution to the Vampire Blog-a-Thon hosted by Nathaniel R. at Film Experience Blog. Check it out for more Halloween goodies.Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht lacks many of the conventional elements of a horror movie. There are no shocks designed to make the audience jump out of their seats, no elaborate special effects, and very little blood. The film's horror is philosophical, and it springs from our most intimate fears (fear of death, fear of madness, fear of entropy). The mummified corpses that open the film stare vacantly at us, as if they were posing an unanswered question. Werner Herzog, who seems constantly driven to stare life's all-encompassing mysteries straight in the eye, is the perfect fit for a vampire film; few directors are so familiar with the uncanny.

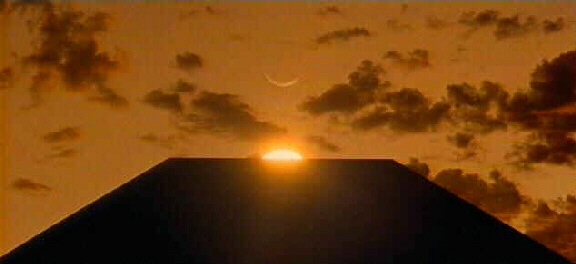

Herzog's remake stays close the the plot of F.W. Murnau's original (although, unlike Murnau, he was allowed to use the characters' original names as the copyright on Bram Stoker's had expired). The film follows Count Dracula (Klaus Kinski) as he journeys to a village in the Netherlands in search of Lucy Harker (Isabelle Adjani), the object of his desire; a plague follows Dracula, killing and consuming nearly everything in his path. Herzog's changes to the film aren't structural but tonal. In Murnau's film, the plague that threatens to destroy an entire village is presented as an occasion for suspense - can anyone stop the monster before it is too late? But Herzog tells the same story with a silent inevitability. As Jonathan (Bruno Ganz), Lucy's husband, makes the long journey through the Carpathian Mountains to his new employer, the prelude to Wagner's Das Rheingold takes the place of typical horror film music on the soundtrack (the piece was also used wonderfully in Terrence Malick's The New World). Herzog subverts our expectations throughout the film; while it's bleak and arguably nihilistic, our response isn't dread, but wonder. Herzog presents fleeting images - a ghoulish cuckoo clock, a bat slowly climbing a curtain - that create a world perched between realty and dreams. Herzog is often labeled a naturalist, but he's really a romanticist - he's drawn to the beauty of decay, collapse, and the end of all things.

At the center of Herzog's vision is Kinski as the lonely Count Dracula. Max Schreck's version of the character is an iconic boogeyman - a feral predator consumed by hunger and singleminded lust. Kinski is equally fearsome, but he's also more recognizably human. Dracula's feelings for Lucy are more romantic than carnal, but he is constantly betrayed by his own nature; the vampire appears embarrassed as he enter's Harker's bedroom late at night for a snack. Kinski weighs down the Count's movements with the fatigue of a thousand years - he almost seems to welcome the respite of a death at sunrise. Kinski is primarily known for his intensity and psychotic temper, but in this and Woycezk (which started filming just days after Nosferatu was completed), he displays astonishing vulnerability. Like the monster in Fuseli's The Nightmare, he is doomed to destroy everything he touches, even that which he desires most.

The saturated reds commonly associate with vampire pictures are absent here, replaced with funereal blacks, cold blues and vacant grays. The always-overcast sky looms over shadowy mountain passes, remote villages and barren landscapes that extend to the horizon. A ghostly palor covers not only Kinski but also Ganz and especially Adjani, whose porcelain beauty has never seemed more tragic. The story progresses with inexorable silence, accompanied by the ethereal score by Popol Vuh. The entire film is driven by a sense of creeping inevitability - only Renfield (played with scenery-chewing glee by Roland Topor, author of The Tenant) possesses a vitality and a gleeful brand of gallows humor. His madness puts him in harmony with the escalating chaos surrounding him.

As the plague and madness overwhelm the village, its residents (including an unusually ineffectual Van Helsing) try in vain to rationalise and solve the problem. A scene depicting members of the upper class going through the motions of a banquet and party among the rats carries a darkly funny charge as a reflection of the ever-changing state of European culture in the 20th century. The vampire here represents not only physical death but also the death of civilization, of enlightenment - of the soul. And Herzog provides no resolution, only the suggestion that evil cannot be stopped, but only travels unnoticed from one place and time to another, carrying out its unknown purpose. Herzog not only honors the original film but surpasses it with his Nosferatu, which is a deeper and more resonant experience; it finds poetry in the horror of the unreal.

The films of Sofia Coppola are remarkable in their stillness. The depressed suburban languor of

The films of Sofia Coppola are remarkable in their stillness. The depressed suburban languor of

Perhaps no artistic medium is as closely tied with the language of dreams as film. This results in an enormous challenge for any filmmaker who attempts to depict dreams in cinema - how does one differentiate a dream from the inherently dreamlike texture of any film without creating something overly self-conscious or contrived? And this is also the larger question for any artists concerned with dreams - how does one deliberately craft the uncanny? With The Science of Sleep, a film about a man who has trouble separating dreams from reality, we are given a possible answer. The film suggests that dreams are no more or less real than waking life; while this is not a new idea, The Science of Sleep is unique in that its dream sequences are not designed for critical analysis; for director Michel Gondry, the mind is magical, and dreams are depicted not intellectually but with a whimsical sense of awe (he took a similar approach to memories with Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind). The result is often wondrous, sometimes frustrating, and ultimately quite sweet.

Perhaps no artistic medium is as closely tied with the language of dreams as film. This results in an enormous challenge for any filmmaker who attempts to depict dreams in cinema - how does one differentiate a dream from the inherently dreamlike texture of any film without creating something overly self-conscious or contrived? And this is also the larger question for any artists concerned with dreams - how does one deliberately craft the uncanny? With The Science of Sleep, a film about a man who has trouble separating dreams from reality, we are given a possible answer. The film suggests that dreams are no more or less real than waking life; while this is not a new idea, The Science of Sleep is unique in that its dream sequences are not designed for critical analysis; for director Michel Gondry, the mind is magical, and dreams are depicted not intellectually but with a whimsical sense of awe (he took a similar approach to memories with Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind). The result is often wondrous, sometimes frustrating, and ultimately quite sweet.

Charlie (Harvey Keitel), the protagonist of Mean Streets, has a habit of holding his hand over a flame, testing himself to see how long he can bear the pain. It's an act of penance, but more than that, it's a confrontational gesture. Charlie is constantly daring himself to look the fact of his own moral fallability and the seemingly predetermined circumstances of his life - what he calls "the pain of hell" - square in the eye. It's a problem we all have to deal with: we don't know why we're here, where we're going, or if we're doing alright, and we all live with it in our own ways. Some of us go to the movies. And the cathartic joy of Mean Streets comes from Martin Scorsese's uncompromising declaration that movies do in fact have meaning. One of the first shots disappears into the blinding light of a film projector; it's a moment that exclaims, boldly and brilliantly, "LIFE IS A MOVIE!"

Charlie (Harvey Keitel), the protagonist of Mean Streets, has a habit of holding his hand over a flame, testing himself to see how long he can bear the pain. It's an act of penance, but more than that, it's a confrontational gesture. Charlie is constantly daring himself to look the fact of his own moral fallability and the seemingly predetermined circumstances of his life - what he calls "the pain of hell" - square in the eye. It's a problem we all have to deal with: we don't know why we're here, where we're going, or if we're doing alright, and we all live with it in our own ways. Some of us go to the movies. And the cathartic joy of Mean Streets comes from Martin Scorsese's uncompromising declaration that movies do in fact have meaning. One of the first shots disappears into the blinding light of a film projector; it's a moment that exclaims, boldly and brilliantly, "LIFE IS A MOVIE!" I recently received my first negative feedback; a person who said he usually enjoys my articles for Focus Arts Monthly objected strongly to my defense of Kevin Smith in

I recently received my first negative feedback; a person who said he usually enjoys my articles for Focus Arts Monthly objected strongly to my defense of Kevin Smith in